As I do this, I'm going through every single thing I'm installing to make sure I do somewhat trust it. That's me ignoring homebrew and where it pulls stuff from when I type something like "brew install calc". What I am doing is checking the provenance of everything else I pull down: validating any SHA-256 hashes they declare; making sure they come off HTTPS URLs, etc. The foundational stuff.

We have to recognise that serving software up over HTTP is something to be phasing out, and, if it is done, for the SHA-256 checksum to be published over HTTPS, or, even better, for the checksum to be signed by a GPG key, after which it can be served anywhere. while OSX supports signed DMG files since OS/X El Capitan, and unless you expect the disk image to be signed, you aren't going to notice when you pick up an unsigned malware variant.

It's too easy for an open wifi station to redirect HTTP connections to somewhere malicious, and we all roam far too much. I realised while I was travelling, that all it would take to get lots of ASF developers on your malicious base station is simply to bring it up in the hotel foyer or in a quiet part of the conference area, giving it the name of the hotel or conference respectively. We conference-goers don't have a way to authenticate these wifi networks.

Anyway, most binaries I am downloading and installing are coming off HTTPS, which is reassuring.

One that doesn't is virtualbox: Oracle are still serving these up over HTTP. They do at least serve up the checksums over HTTP, but they don't do much in highlighting how much checking matters. No "to ensure that these binaries haven't been replaced by malicious one anywhere between your laptop and us, you MUST verify the checksums. No, it's just a mild hint, " You might want to compare the SHA256 checksums or the MD5 checksums to verify the integrity of downloaded packages".

Not HTTPS then, but with the artifacts something whose checksum I can validate from HTTPS. These are on the dev box, happily.

But here's something that I've just installed on the older, household laptop, "dogbert": Garmin Express. This is little app which looks at the data in a USB mounted Garmin bike computer, grabs the latest activities and updates them to Garmin's cloud infrastructure, where they make their way to Strava, somehow. Oh, and pushes firmware updates the other direction.

The Garmin Express application is downloaded over HTTP, no MD5, SHA1 or anything else. And while the app itself is signed, OSX can and will run unsigned apps if the permissions are set. I have to make sure that the "allow from anywhere" option is not set in the security panel before running any installer.

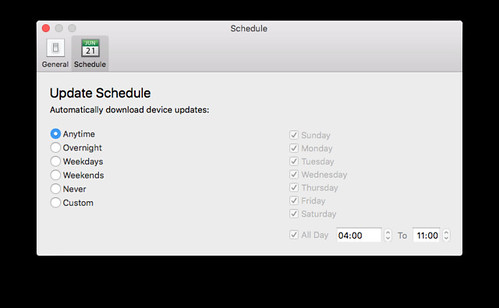

Here's the best bit though: that application does auto updates, any time, anywhere.

Which means that little app, set to automatically run on boot, is out there checking for notifications of an updated application, then downloading it. It doesn't install it, but it will say "here's an update" and launch the installer.

Could I use this to get something malicious onto a machine? Maybe. I'd have to see if the probes for updates were on HTTP vs HTTPS, and if HTTP, what the payload was. If it was HTTPS, well, you are owned by whoever has their CAs installed on your system. That's way out of scope. But if HTTP is used, then getting the Garmin app to install an unsigned artifact looks straightforward. In fact, even if the update protocol is over HTTPS, given the artifact names of the updates can be determined, you could just serve up malicious copies all the time and hope that someone picks it up That's less aggressive through, and harder to guarantee any success from subverted base stations at a conference.

Rather than go to the effort of wireshark, we can play with lsof to see what network connections are set up on process launch

# lsof -i -n -P | grep -i garmin

Garmin 9966 12u 0x5ccb80e39679382b 192.168.1.18:55235->40.114.241.141:443

Garmin 9966 16u 0x5ccb80e39679382b 192.168.1.18:55235->40.114.241.141:443

Garmin 9967 10u 0x5ccb80e396b4a82b 192.168.1.18:55233->2.17.221.5:443

Garmin 9967 13u 0x5ccb80e39687182b 192.168.1.18:55234->2.17.221.5:443

Garmin 9967 15u 0x5ccb80e3910b7a1b 192.168.1.18:55236->2.17.221.5:443

Garmin 9967 16u 0x5ccb80e39669e63b 192.168.1.18:55237->2.17.221.5:443

Garmin 9967 17u 0x5ccb80e396b4a82b 192.168.1.18:55233->2.17.221.5:443

Garmin 9967 18u 0x5ccb80e39687182b 192.168.1.18:55234->2.17.221.5:443

Garmin 9967 19u 0x5ccb80e3910b7a1b 192.168.1.18:55236->2.17.221.5:443

Garmin 9967 20u 0x5ccb80e3960c782b 192.168.1.18:55238->2.17.221.5:443

Garmin 9967 21u 0x5ccb80e39669e63b 192.168.1.18:55237->2.17.221.5:443

Garmin 9967 22u 0x5ccb80e3979fa63b 192.168.1.18:55239->2.17.221.5:443

Garmin 9967 23u 0x5ccb80e3910b4d43 192.168.1.18:55240->2.17.221.5:443

Garmin 9967 24u 0x5ccb80e3910b4d43 192.168.1.18:55240->2.17.221.5:443

Garmin 9967 25u 0x5ccb80e3979fa63b 192.168.1.18:55239->2.17.221.5:443

Garmin 9967 26u 0x5ccb80e3960c782b 192.168.1.18:55238->2.17.221.5:443

2.17.221.5 turns out to be https://garmin.com/, so it is at least checking in over HTTPS there. What about the 40.114.241.141 address? Interesting indeed. tap that into firefox as https://40.114.241.141 and then go through the advanced bit of the warning, and you can see that the certificate served up is valid for a set of hosts:

dc.services.visualstudio.com, eus-breeziest-in.cloudapp.net, eus2-breeziest-in.cloudapp.net, cus-breeziest-in.cloudapp.net, wus-breeziest-in.cloudapp.net, ncus-breeziest-in.cloudapp.net, scus-breeziest-in.cloudapp.net, sea-breeziest-in.cloudapp.net, neu-breeziest-in.cloudapp.net, weu-breeziest-in.cloudapp.net, eustst-breeziest-in.cloudapp.net, gate.hockeyapp.net, dc.applicationinsights.microsoft.com

That's interesting because it means its something in azure space. in particular, rummaging around brings up hockeyapp.net as a key possible URL, given that Hockeyapp Is a monitoring service for instrumented applications. I distinctly recall selecting "no" when asked if I wanted to participate in the "help us improve our product" feature, but clearly something is being communicated. All these requests seem to go away once app launch is complete, but it may be on a schedule. At least now I can be somewhat confident that the checks for new versions are being done over HTTPS; I just don't trust the downloads that come after.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are usually moderated -sorry.